H 1947 – 1950)

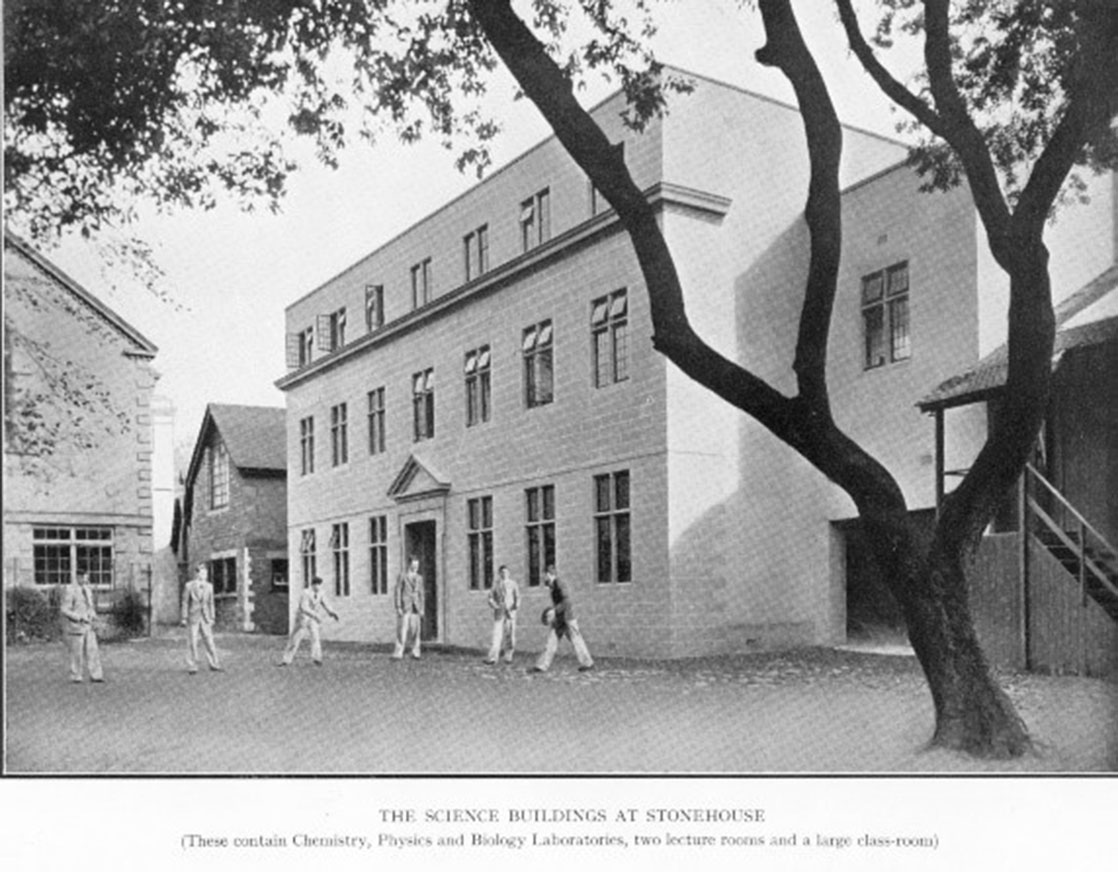

I took the Common Entrance examination in the summer term whilst at Glaston Tor school and, soon after my 14th birthday, I started at Wycliffe College, Stonehouse, in Gloucestershire in 1947. This was a bit of a tradition in my family as my great uncle Fred went there in 1892, just 12 years after it was founded by the Sibley family. He was followed by my father, Henry Eric, who was there during the 1st World War, 1915-17, then his brother, my Uncle Ronald, from 1921-24. Both my father and my uncle were under the headmastership of the second family member to hold the post, W Arthur Sibley, known as W.A.S. and he only retired at the end of the previous term to me going there. Another old boy of the school was appointed to the position, S.G.H. Loosley, whom we referred to as “Stan”.

Although I had sat the scholarship exam. I obviously did not quite reach that standard but found myself in the Remove Form, as opposed to the lowest form in the senior school, the Fourth, and I was therefore one of the youngest in the class. This only gave me two years to prepare for my School Certificate exams.

All my family had been in Haywardsfield house, first built in 1885, so that is where I also went. There was accommodation for around 50 boys in this house. The original School House had a few more, as did Springfield, the vegetarian house, situated across the road behind the main school. The most recent house, when I went there, was Ward’s, near the main entrance to the school grounds. The housemaster of Haywardsfield was R. B. Evans, who, having served in the R.A.F. in the war, ran the school A.T.C. (Air Training Corps). I obviously did not upset him as he almost invariably gave me a good report at the end of each term.

At that time, we all had our meals in our own houses, with about 10 boys sitting at each table, overseen by a prefect at each meal. After Glaston Tor, I found the food so much better and, although we each had coupons for our sweet ration, on many occasions I was quite happy to sell this to another boy who could then use them in the school tuck shop, run by Mrs Murdin, the school groundsman’s wife. We all slept in dormitories with about 8 beds in each although on each floor there was a single bedroom where either the head boy of the house or his deputy slept.

One of the fun occasions was when we had a fire drill. From each of the dormitories there was a device attached to the side of one of its windows. This had a rope with a sling which you placed under your armpits before climbing out of the window. The rope unwound slowly as you descended to the ground outside. As you went down, the other end of the rope returned to the top. By reaching out of a lower window and anchoring the returning rope to a bed this stopped the poor descending lad from moving either up or down. The preferred victim would have been one of the prefects, the senior boys in the house!

For my first term at Wycliffe my parents had taken me by car. Coming home again, at Christmas, I was due to catch the train. Not realising that Stonehouse had two railway stations, both the London, Midland and Scottish and the Great Western, I went to the wrong one to catch my train home. Back to the school feeling very foolish, Mr Evans had to ring my parents, then find out when the next train ran to Bath for connection with the one to Evercreech Junction. Luckily there were later ones and I made it, just a bit later than planned.

Those taking the train home at the end of term were expected to get their trunks packed well before the last day at school. A lorry would come from the railway company and trunks were all sent to our home station by what was called ”Passenger’s Luggage in Advance”. All I had to carry home was a small case, in my case a “Gladstone” bag, which, like my trunk, had previously been used by my father before me

The school had only returned from its war-time evacuation to St David’s College, Lampeter, a year before I joined. The Air Ministry’s use of the premises throughout the previous 7 years was still very much in evidence, even some of the brick-built blast walls in front of the downstairs windows. Many of our classes were held in the wooden huts remaining on the edge of the cricket pitch in front of School House. They were certainly not very well insulated, only too obvious during the winter months.

Whilst the school was away in West Wales the school chapel had, unfortunately, been severely damaged by fire with only the tower, a memorial to the old boys lost in the 1st World War, left standing. Whilst I was at Wycliffe a start was made to restoring this building to its former glory, this work overseen by the craft master, P. J. Parrott, who also oversaw the school Young Farmers Club, about which, more later on. Although most of the restoration was done after I left school, I still followed its progress with interest. Timber was still very much in short supply due to the rebuilding in the cities which had been destroyed by enemy bombing but, using the Old Boy network, some large reclaimed timbers were obtained from a disused jetty on the Isle of Wight and were delivered to the school pre-cut to shape. A new set of chairs was also required and these were produced from reclaimed timber and delivered to the school in kit form where the boys assembled them in woodwork classes.

My parents had budgeted for me to be at Wycliffe for just three years, not imagining that I would be in any class but the lowest when I went there. Perhaps this was because my father had, himself, only stayed for three years before having to leave, due to his father’s illness, coming home to the farm. This was then a slight problem as, after taking my School Certificate, I was now in the Sixth Form but with only one year to go before I left; and studying for Higher Certificate was based on two years of work. It was decided that I could take the Geography exam in one year and I glad to say I ended my schooling with a certificate to show one subject passed successfully. I thoroughly enjoyed higher geography, learning about glaciers, ox-bow lakes, roche moutonnee and why towns developed in the places they did. All good practical stuff.

I played rugby in the winter term, although it was not really my sport, and I see that I did manage to play in the house matches, if only in the third team. In the school shop there was set of 20 runs on courses around the immediate district, the longest of which was 12 miles, each to be completed in an afternoon. During the spring term in my final year I manged to complete all twenty of these which was quite an achievement. In that summer term I took up rowing, which was on the Berkeley-Gloucester canal where the school had its boathouse. We used to cycle down there and spend a very pleasant afternoon rowing up and down the canal, just keeping an eye open for the large commercial barges that still used that waterway. If one paddled far enough down one could catch a whiff of the delightful smell which emanated from the Cadbury’s chocolate factory based alongside the canal.

Although rarely suffering from ill-health, I did have a couple of spells in the school sanatorium. With chickenpox I only had about seven spots and really did not notice having the infection but with measles it was a different matter. Initially one was put into isolation, in a darkened room, with fellow sufferers, in order to lessen the danger to one’s sight. In charge was a fairly strict matron who, later, whilst we were in recovery, we greatly displeased. She was showing some visitors around, probably potential pupil’s parents and, coming to our room where we were sat out, we failed to stand up. Well, we were in recovery, after all! When the visitors had left, we certainly got a good telling off for our lack of respect!

Although we occasionally swam whilst I was at Glaston Tor School, I did not learn to swim. Basically, there were no easy facilities available for swimming whilst at home, no one we knew had a swimming pool in those days. Therefore, it was not until going to Wycliffe that I learnt to swim. This I did during my first summer term; I have never moved on from the basic breast stroke and much envied those who could race away doing a crawl, something I never mastered. Anyhow, during the summer of 1949 we were expected, having learnt to swim, to learn to life-save in preparation for taking the examination for the Bronze Medallion given by the Royal Life Saving Society. One of the tests was to be able to dive down to four feet and retrieve a hessian wrapped brick. Unfortunately, I was the first candidate on, the examiner proceeded to throw the brick in the deep end, all of six feet six inches (2 metres) down. I had never dived this deep before but, as is said, when needs must… I dived and successfully brought it up. Anyhow I passed the exam and have the medal to prove it.

My main joy whilst at Wycliffe was being a member of the school Young Farmers Club based on a strip of land across the road from the school grounds between the railway line and the old, disused, Stroud Water Canal. A large building alongside the canal was still there, the original school boathouse from which the boys rowed as well as swam on and in the canal in earlier days. Also remaining, the original concrete lined, swimming pool which was fed from the canal. I remember filling this in using only spades and wheel-barrows to reclaim that bit of land for our farm.

We kept pigs and poultry, the former mainly fed on waste from the school kitchens together with the experimental use of the grass mown from the school’s sports pitches and lawns. These we used to ensile, with stock-feed potatoes sandwiched between layers of the grass. The heat generated by the process cooked the potatoes nicely. Stock-feed potatoes were available to farmers, after being rejected for human consumption, coloured with a purple dye to prevent re-sale. The school kitchen waste was boiled in a large swinging container using steam from a wood fuelled boiler alongside. The cooked product was then mixed with meal and was either fed to the pigs along the feeding troughs of the sties attached or to the poultry. At times, when there was not sufficient food waste, we cooked potatoes instead. Mr Parrott was quite innovative and produced a press to mash the cooked potatoes by pressing them through a criss-cross of thin wires. Known as “Polly Parrott’s Perfect Potato Press for Producing Perfect Poultry Pellets”. Being made entirely of wood it was, unfortunately, not really strong enough to withstand the pressures put on it!

One of my friends while at Wycliffe was Michael “Ben” Keene, a Y.F.C. member, whose family farmed, and still do, at Highnam, just across the river at Gloucester. They grew a large acreage of potatoes and each autumn, after the crop had been harvested and the land cultivated, a group of us Young Farmers used to cycle across and go “Gleaning”, i.e. picking up any potatoes that had been missed, or rejected because of damage, which we bagged up and they were brought back to school to feed the pigs and hens. A cheap source of feed.

We boys were totally responsible for feeding, bedding and mucking out throughout the term time as well as seeing to the laying hens. The hens were in moveable houses in outdoor runs on the rest of the property. One very memorable animal was a very bad-tempered cockerel. He obviously took a strong dislike to us boys and he would attack, coming at one at about waist height. Getting one’s timing right, a well-placed kick would catch him in full flight, giving a few moments respite before he came again.

Much of the building work around the farm we undertook ourselves, I was particularly proud of a gate I made, and concrete mixing and laying were all skills we learnt from the master in charge, “Polly” Parrott, the craft and technical drawing master of the school. He was a man who seemed to be able to turn his hand to anything practical and a great inspiration to me in my later life. He once told me that the important thing was to have the confidence to begin a job, everything else then fell into place. Having the farm away from the school meant that we had a lot of freedom, but also responsibility, but it gave us a lot of fun and it was not without its benefit to our education.

I am not certain as to how it was organised but the Y.F.C. managed to have a day away from school visiting the Standard Motor Company in Coventry. At that time the Ferguson tractors were being manufactured there in another part of the factory but, compared with more recent tractors, they were very simple machines. All I really remembered was seeing the Standard Vanguard assembly line and watching the man whose duty was to check the doors fitted correctly at the end of it. Beside him he had a selection of wooden wedges, choosing one, he placed it in position and then forcibly slammed the door shut. Presumably this had the desired effect but it did little to enhance my faith in British made cars.

There was a strong spirit of volunteering in the ethos of the school. I remember a group of us helping create some new grass tennis courts in front of the school chapel, stripping the turf, levelling the sloping site with wheelbarrows and hard graft and then re-turfing the site afterwards. We also undertook to dig out some very large elm tree stumps in the school playing fields in the Berryfield. A hired “Monkey” winch was placed around the stump and we dug round the roots, cutting off each one as we came across it until, eventually, we were able to drag the whole thing out of the ground in preparation for a new building to be put on the site.

Each evening, after tea, we had a compulsory hour of “prep” and then an hour of doing things from a choice of subjects, mostly of a craft nature. I belonged to what was known as the “Woodwork Guild” where, in the school woodwork workshop, I made two bed-side lamps, one in the design of a rabbit. Also, during another term, a rush-seated stool. All these were made from off-cut timber donated to the school.

Also, in my last year, I belonged to the Science Society. We were allowed to use the chemistry laboratory for various, generally unsupervised, experiments. Glass blowing was a great favourite using the Bunsen burners but eventually this was stopped when “Spud” Murphy, the chemistry master, realised that his stock of glass tubing was being seriously depleted.

If one wanted to, one could join the Printers Guild where a regular school newspaper was designed and printed, all hand-set from lead type and printed on a foot-operated printing machine

Before the outbreak of war, the school had taken groups of boys abroad to many parts of Europe at minimal cost to their parents. I went on one of the first post-war summer tours. A large party of us travelled by train down through France to a little fishing village on the banks of Lake Geneva, Excenevex, and camped for a week. We had beautiful weather and were able to swim and enjoy ourselves. One of the boys, as is their wont, managed to overdo the consumption of the local brandy and was quite ill, a lesson well learnt. The one drawback I remembered about that camp-site was that, during the night, some unseen creatures would emerge and chew the surface dressing off any leather wear such as shoes and belts that were left on the ground.

After a week on this site, we took the train into Switzerland where we caught the Mer De Glace – Chamonix mountain railway which wound its way up to over 3000 feet. One could look down and see the back of the train still entering the tunnel beneath us as we emerged back into the light. Then on the Martigny – Chatelard rack railway ending up in a small village, Les Marecottes, near Martigny, high in the Alps, staying in a very spartan hotel. Having suffered from neglect due to the war, the bedrooms did not even have any furniture; we all slept in our sleeping bags on the floor. It was a very pretty mountain village, looking exactly like would imagine an alpine village to be. In the little shop I recall one of our more senior boys attempting to use his school-boy French to ask for some chocolate. The young lady behind the counter listened carefully: then answered him in near perfect English, much to the amusement of us watching.

On looking through the photos I took with my Ensign camera, with its small square pictures, I see that we must have made various day trips. A picture of the glacier, the Mer de Glace, another the Barberine Lake, now called Lac d’Emosson, as well as ones around the village. Dominating the horizon Mont Blanc, seemed to be perpetually in view.

On our way home, via Martigny, we took the ferry down the lake to Geneva where we had a little time to look around before taking the night train across France to Paris. We certainly did not have any luxuries; overnight we slept on the luggage racks, on the seats or on the floor in the corridor. Arriving in Paris in the early morning, a quick tour of the city had been arranged and we had time to do a little shopping before continuing our homeward journey.

Going through customs on the English side was a new experience. I had bought a very small cuckoo clock in Switzerland and I was rather hurt to be charged 10 shillings customs duty on it. I was even more aggrieved when I spoke to my friend, John Daniels, who had bought an identical one, to discover that his had been allowed through without any payment at all!

At Wycliffe, with notice only being given the evening before, the school authorities would announce that the following day would be a whole holiday. These did not occur too often, as you can imagine. My father told me, in his time there, the school tradition was that if, when the sun first rose in the morning, there was a completely cloudless sky, a whole-day holiday would be declared; this never happened when I was there and I don’t think it did in his day either. Even now I regularly check but I have yet to see such a thing, invariably there is a wisp of cloud somewhere on the horizon.

On these days off, we each had to decide what we intended to do and write it down in a book provided; immediately after breakfast we collected our packed lunch and off we went. On one of these days, a group of three of us decided on taking a long cycle ride which took us, via Gloucester, across the river to Tewkesbury, Worcester, Evesham, Cheltenham, Cirencester, Avening and back to school, something just over 100 miles according to the cyclometers on our bikes. Peter Holburn, the keen cyclist in our group, went out again, after we had reported back at school and had some tea, and did another 35 miles that evening. In my last two years at Wycliffe I clocked up over 2000 miles on my old bike.

On another occasion, three of us decided to walk to Gloucester along the, not very busy, roads before coming home again by bus. At mid-day we were sat in the sunshine beside a hay rick, eating our packed lunch, when the local copper arrived on a bike and asked us what we were doing! He probably thought we were bunking off from school for the day. After a little explanation about whole-day holidays, etc. he accepted our reason and left us to finish lunch in peace.

After leaving school, just before my 17th birthday in July 1950, a group of four of us took a camping holiday in Scotland. The father of my friend from school, John Daniels, very kindly lent us his Land Rover, registration number MAD 890, and John, David Johnson, also from Wycliffe, and a friend of his, Peter Jones, and I loaded the vehicle up with all our kit. It was so full of tents, sleeping bags and the like and three people across the bench seat at the front, the only room for the fourth person was to lie on top of all the luggage in the back. For this we took it in turns. For some reason we decided to drive all night and I well remember being the passenger in the back as we arrived along bumpy cobbled streets in Glasgow at around seven o’clock in the morning. The suspension on those original Land Rovers was certainly not made for comfort. We had a great time even, one evening, camping on a headland overlooking the ferry point looking across to Skye. With time to spare, and the long light evenings, we took the ferry and watched the final of a local football league match on the island. We decided that they certainly did things differently in Scotland. We previously had believed that you only ever played football in the winter months.

All of us had been brought up to expect to go to church weekly, so one Sunday we all went to the local kirk. When it came to singing the first hymn, we were most surprised to find that there was no organ, just a lead singer who guided the congregation through the tune. Apparently, this was quite normal in small churches in Scotland, I later learnt. One night we camped in a valley, Glen Nevis, beneath Ben Nevis and the following day we, being all very fit, had no trouble climbing it. At the top, almost unbelievably, we met a school-friend of Peter Jones, George Walton, (in the dark top in the picture). To celebrate this occasion, a small bottle of whisky was produced and rapidly consumed. Much later, George Walton came back into my life in completely different circumstances.

On the way home we stopped in the Lake District and, with a little time to spare, we ran up Helvellyn and back, another proof of our fitness at that time.

Since that time I have continued to visit Wycliffe, initially to attend Old Boys Days, but much later when our son, David, went to Wycliffe, in both the Junior and Senior schools. 1970-87.

Only fairly recently, David’s younger daughter, Erika, whilst at school at Monkton Combe in Bath, came to Wycliffe to play the school at Netball and David and I decided to come to watch. With mixed loyalties I was torn as to which team to support. Wycliffe won but I would have been equally pleased if my grand-daughters team had done so. As visitors we were then entertained to a light tea with the teams involved, another new experience for me.

On leaving Wycliffe, I spent a year working on a mixed dairy/arable farm in Wiltshire before attending the Somerset Farm Institute (later known as the Somerset College of Agriculture) on a one-year course, coming home to the family farm in 1952.

I took a fairly active part in the local Young Farmers Club and I was rewarded by winning an 8-month scholarship to Australia and New Zealand in 1958. Travelling out by P&O liner through the Suez Canal and calling in at Mumbai (what was then called Bombay) and then Colombo. Two and half months staying as a guest of Young Farmers followed in South Australia, before moving on to New Zealand where I spent a further three and a half months. Constantly moving after either a week, or sometimes two, at any one place and really getting to know the farming over there. I then returned home across the Pacific and the Atlantic by way of the Panama Canal. Altogether a marvellous, life-changing, experience.

Marriage to Mary, a fellow Mid-Somerset Young Farmers Club member in 1959 and then settled into family life.

With three children, the eldest of whom is David, an Old Wycliffian himself, now running the farm. The two girls, having gone away to university, married fellow students and now live a distance away although we do see them on a fairly regular basis.

In the past, I have been involved with politics as well as voluntary local and farming affairs. As well as being on the Council of the Royal Bath & West Show Society and actively involved in the museum world. I spent sixteen years as treasurer of Wells Museum and twelve years as a Somerset County Councillor, as well as being Church-warden of our little village church, on and off for 40 years. Even so, I was very surprised to get a letter in 1913 from the Cabinet Office asking if I would be willing to accept an award as I had been recommended for it! It did not take any time at all to reply to that one.

Duly called to Buckingham Palace that autumn where Prince Charles pinned on my O.B.E. for “Services to Agriculture and the Community in Somerset”. A very proud moment.

Mary and I now live in a converted farm building at the higher end of the farm and remain as senior partners in the business although not interfering with the day to day management of it. I still act as chairman and book-keeper of a joint venture company we set up with two other local farmers growing arable crops in the immediate area.

Unusually these days, I still live in the same village I was born in. In fact, I can see from where I now live, every house I have called home for the past 86 years.

Allen Cotton

Haywardsfield

1947-50