S 1944 - 1946

Varied beginnings

It was soon after my fourth birthday that we moved to Paris where we lived for four years followed by a six-year term in Lausanne. By the time I was 14 and I was fluent in French but knew no English whatsoever. As the second World War started, we virtually became refugees with no means by which we could return to the UK. Quite unexpectedly, my father heard of a last civilian transport from St Malo to Southampton and the whole family was able to board the ship for a safe night crossing. Miraculously, with all our luggage.

Our first home was in Hadley Wood near Barnet. My brother and I were able to follow a year in the Hadley Common school where we gained the elements of the language in that small two-class school. After twelve months I was transferred to the Barnet Grammar School, one of the best schools in North London. I found it very difficult to adapt to the strict rules and discipline of the school and, obviously, I was quite out of my depth in all subjects. It was years before I found out why big boys would bowl me over on a grassless field and I had to push others boys’ btms at the far end.

There followed a move to Norwich and a year or two mostly spent in the Air Raid shelters of the Norfolk and Norwich Grammar School before we moved on, yet again, to Cambuslang this stime, a suburb of Glasgow. The change of language the change of schools, the nightly bombing raids whist we were in London and the unsettled life we led for those years, must have affected my emotional development in some way. My next school was Rutherglen Academy a few miles away. The intermittent bus services meant I often could not get to school on time. Some teachers’ use of physical punishments (The belt!) to mark any student’s late arrival regularly aggravated the situation

By the time I was sixteen it must have become obvious to my parents that I was going through a particularly difficult time. It was then that my father called for the assistance of a skilled adviser who proposed a change of venue. I should move to a more stable environment, so I was sent to Wycliffe College, which, at that time, had been evacuated to St. David’ in Lampeter. Life was to change dramatically for the better.

Life at Lampeter and the move back to Stonehouse

I was given a place in Springfield and, since the dormitories were full, I boarded with Mr. Goodwin, one of the teachers, and his family. This new life away from home had some beneficial effects and helped me to clear up some of the problems.

I was very soon absorbed by the daily routine of the school, and adapted to some of the more peculiar items on the programme, such as Prep for half an hour at 7.00am every weekday! I also found the teachers made valiant efforts to bring me up to the level which the other students in my class had attained.

Half-hols were wonderful opportunities to discover the wonders of the neighbouring countryside as we roamed all over on our cycles. There were many extracurricular activities which were always interesting. New friends guided me to an abandoned gold mine, supposedly permanently closed; where we dug for gold nuggets, but only found ancient gold veins in the very solid granite. We also found piles of ex-military items such as smoke bombs which we lit with delight, shrouding the valley in smoke.

Many of us joined the ATC, (Air Training Corps). We wore much the same light-blue uniform as the airmen. Only the buttons were of a different colour. We marched and trained, as many were doing during those years, ready to be ‘called up’ if the war lasted long enough.

At the annual camp we had opportunity to share the life of the airmen in every way, including taking short flights in a number of planes. A ride in the Tiger Moth was made even more exciting by the pilot turning the plane upside down when the engine would immediately stop until a more usual flight pattern was resumed. The fuel tank was in the top wing of this small biplane!

On one occasion I was able to pilot a Doncaster bomber for thirty minutes or more. After a few minutes in the air, the pilot left his seat and joined the rest of the crew to play cards in the rear of the plane. I just tried to keep it on as even a keel as I could, my eyes glued permanently on the controls. On returning to the cockpit, the pilot could not work out where we were! Throwing the plane this way and that, he finally recognized a landmark and, with a few unprintable words, turned for home. Flying a plane was easy!

I also joined the Scouts and obtained my King’s Scout Badge after spending weeks trying to pass the ‘Estimation’ test. Whenever I tried to ‘calculate’ in what I thought was a sensible manner, I was told I had to ‘estimate’! I failed week after week but finally managed to convince my referee.

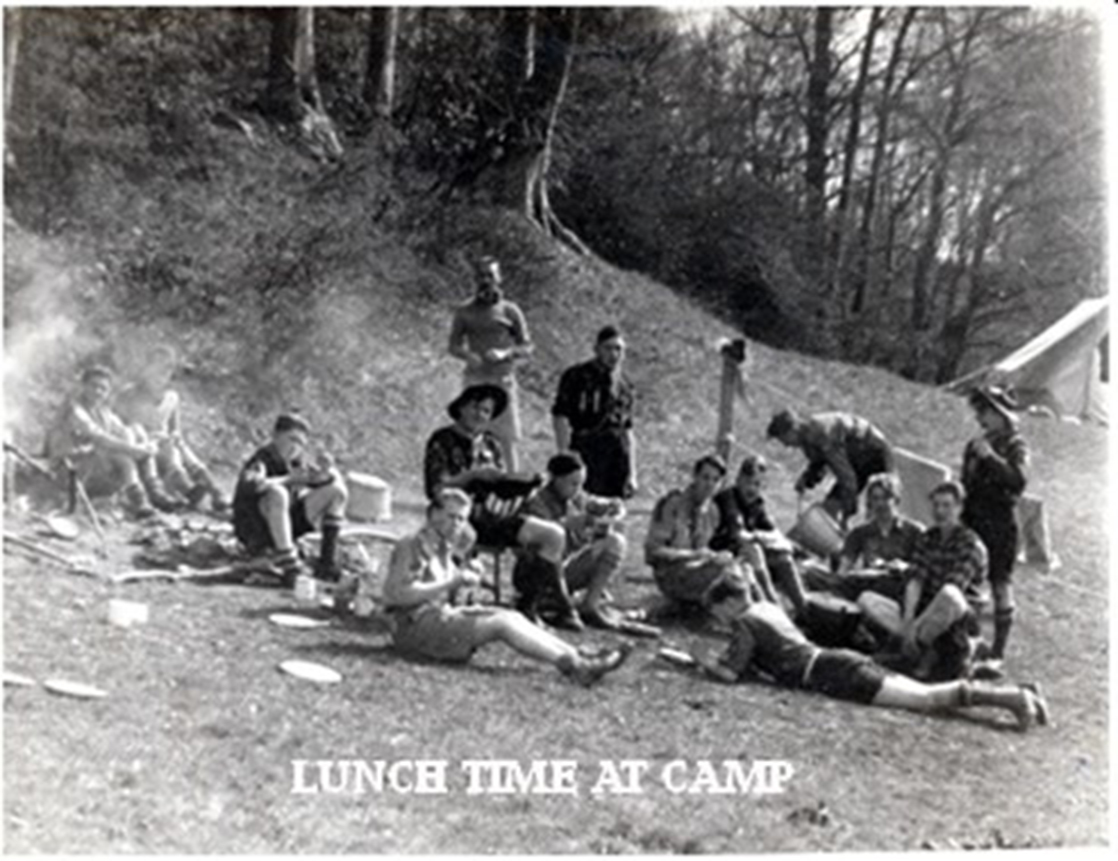

In June 1944, the scout troop encamped near the sea for a few days. I was nominated cook for the patrol which was camped nearest the beech. The constant wind made it impossible to keep the sand out of the food and we were soon known as ‘the Silicate Patrol’. Great news reached us on the 6th of June 1944. The day the long awaited ‘Second Front’ was launched, with the Allies landing in Normandy. This long-awaited day had finally arrived. As the news spread in the camp, we celebrated by launching our tin plates into the air as tin plate Frisbees or, more accurately, as ‘Unguided Missiles’. The school year ended with my obtaining two distinction and five passes in the School Certificate which was testimony to the teachers’ dedication and determination and some hard work on my part.

After twelve months, the school returned to Stonehouse, where my brother David joined me. Working even harder, I obtained two Distinctions and three Credits in the Higher School Certificate in the one year, mostly thanks to Mr Evans, the History & Geography teacher who used to boast ‘None of my boys has ever failed an exam and you won’t be the first’. I felt I had something to show for my school career. The two years at Wycliffe were of the very best I could have hoped for. They were enhanced with plenty of sports, activity clubs and organised cycle rides on ‘Half or ‘Whole Hols’.

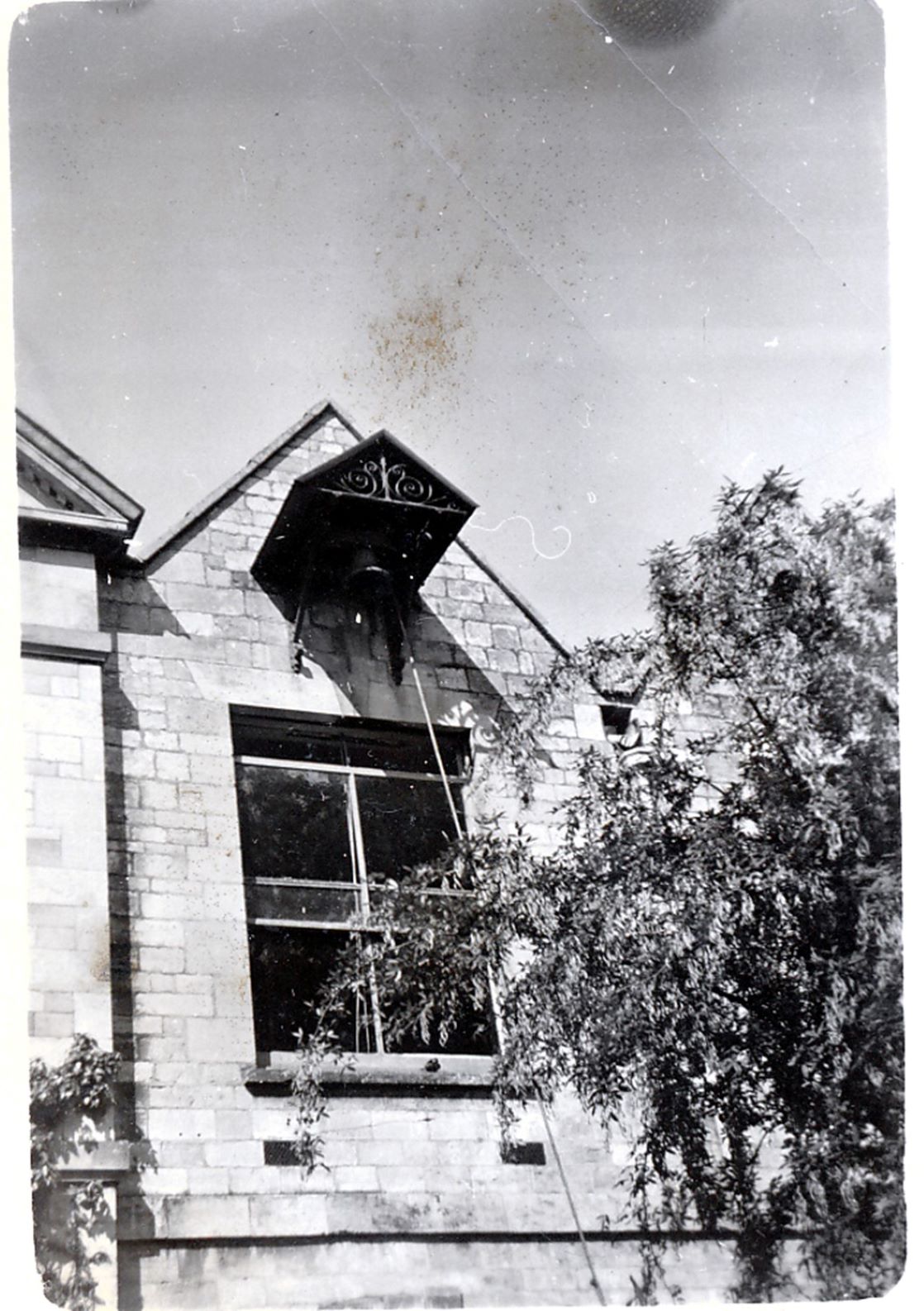

I joined the Photo Club with my box camera. Among other things, I ‘invented’ what I claim to be the first ‘remote control camera, (as shown in the photo!) The word ‘Selfie’ had not been invented at the time, but I suppose that was what it was!

Who was W.A.S?

The Headmaster, (and Housemaster for Springfield, a vegetarian house), was William Arthur Sibley (or WAS for short) The son of the school’s’ fouder, he was one of the more modern educators of his day. WAS loved cycling and led long expeditions to all parts of Wales. He often boasted in his broad accent ‘Err, I can remember when I was the fastest thing on the road’. He loved his work and he loved animals. He would stop to pick a worm and remove it to the border for instance. One evening, four of us in our dormitory were following a moth with our torches as the searchlights followed bombers in London. As it flew about the room, we were making a good deal of noise. WAS came in ‘Wha, Wha, Wha, what’s all that noise about?’ he muttered as we pointed out the moth ‘Put those lights out, you will hurt its eyes’ came the swift order.

When the school returned to Stonehouse my brother and I returned from holidays a few days before the autumn term started for some unknown reason. We helped with various jobs for a week or two wherever we were needed. We must have got into some sort of trouble on one occasion, so we were made to work in the garden. Dave was stung by a bee and complained to WAS. He promptly replied: ‘Serve you right. Now that bee will die because of your bad behaviour.’

Grace always preceded the vegetarian, meal at midday. It was nearly always a long Latin prayer whilst we waited impatiently for the food, or it was the shortest grace I have ever heard, ‘Benedictio benedicat’. I presumed it meant ‘Bless these blessings’ or words to that effect.

The fact that, unlike other public schools, there were no ‘fags’ and no corporal punishments was a real advantage. Discipline was maintained by the imposition of ‘Blogs’, a run round the cricket field. On Saturday afternoon. Blogs were awarded by teachers and prefects for any infringement of the rules, usually three at a time, or six or ten for major departure from the rules. Twenty blogs or more, you were ‘gated’ and had to report to the Duty Prefect within 30 seconds whenever the school bell was rung any Wednesday or Saturday afternoon, and many evenings. This limited your free-time activities somewhat! The ‘blogs’ also ensured the rugby teams were amongst the best in the county!

Hitch-hiking was a fairly common means of transport in those days, so I decided to use my initiative and return home from the ATC camp in South Wales to Glasgow, beginning with a flight from Cardiff to Oxford, just over 100 miles. Then it was on the road. Good fortune meant I was able to take a lift on the back of an open truck for over 100 miles, arriving in Birmingham about 11pm. Trying in vain to get a lift at that time of night resulted in my being accosted by a policeman who enquired as to what I was supposed to be doing standing in the middle of the road, under the rain, after 10pm He soon stopped a car and required the driver to take me to a Service Men’s Shelter in the centre of Birmingham. Once through the door, I stood as near to the ‘Booking’ hatch as possible, hoping no one would notice I wore the wrong kind of tunic buttons but also that I was obviously far too young to be an ‘airman’. The next morning as I awoke, I found my face was covered with pustules full of puss. The truck’s exhaust must have entered every pore on my face. I rubbed my face hard, got my breakfast, and hitch-hiked on to Glasgow.

The Scout Troop in 1944

A life fulfilled

Following school, I trained and worked as an instructor for physically handicapped and war wound boys in France. I later became a Salvation Army Officer when knowledge of the French language led me and my wife Ruth to work in the Congo-Brazzaville. A later appointment took the family to Italy where, through generous gifts from the USA, we were able to build a large village with some 40 to 50 homes as well as five community centres in various parts of the 1981 earthquake area. We also built a furniture factory to provide work for the unemployed.

Knowing English, French, Italian and some Norwegian, our Headquarters appointed us to Germany as Territorial Commander for our last appointment! In addition to the multiplicity of various tasks the job required, our three last years of active service gave us the opportunity to recover and renovate twenty-two properties which had previously been expropriated by the Folk Solidarity Party forty years previously.

My two years at Wycliffe proved to be a very positive experience and I am grateful to the teaching staff and to those who made the sacrifices that allowed me to profit from the two very short years spent at the school.