(W 1950 - 1955)

Richard wrote to us in September about his Wycliffe memories and life experiences. We loved hearing about his adventures!

Wycliffe Days and Beyond

John Cleare’s 1951 photograph of our small Wycliffe party of young rock climbers guided by Bertie Robertson prompts me to recall those adventurous years, not only in Wales but in term time and, of course, in later life.

Compared with today we had immense freedom, in those immediate post war years, to explore and take risks. Do many boarding schools now say their charges, ‘It’s going to be a nice day tomorrow, so we’ll make it a holiday. Go off into the countryside, bike or on foot, enjoy yourselves and gain a new experience.’?

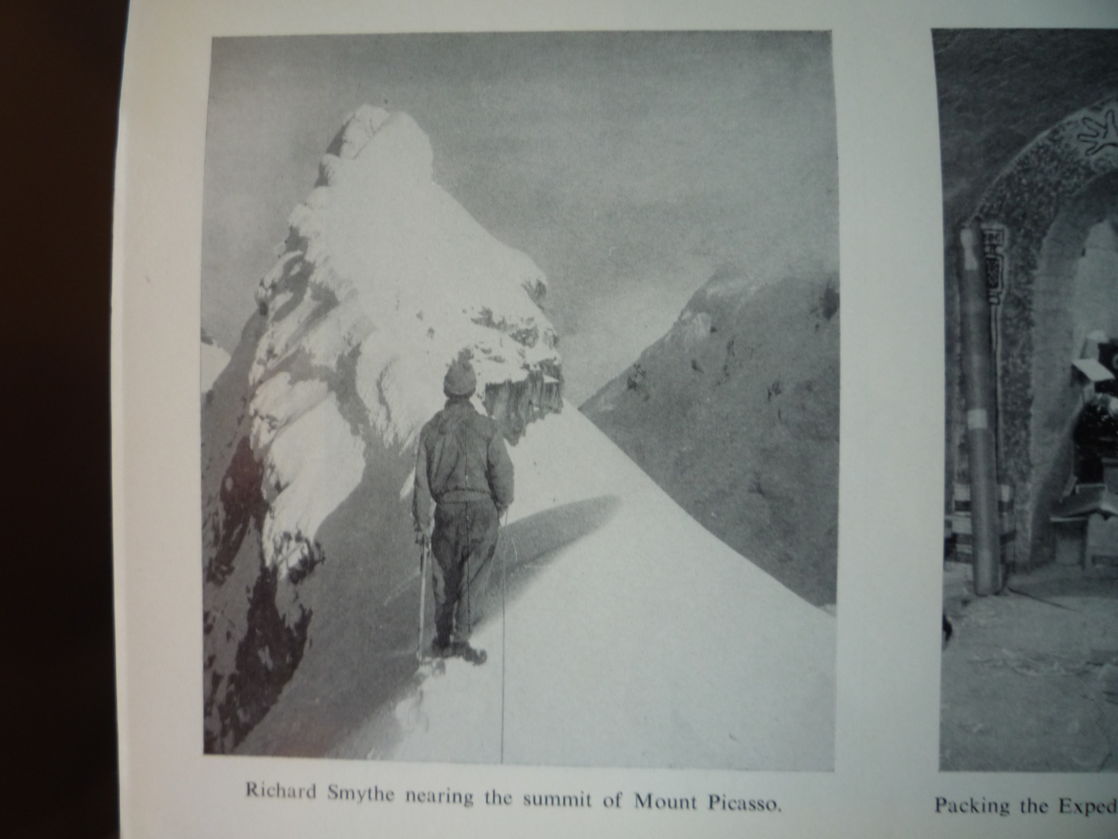

I used my knowledge of rocks once to cycle to Bristol with Graham Fawcus to climb the limestone cliffs of the Avon Gorge. Graham had no previous experience, as far as I know, but proved to be a relaxed, natural climber. Closer to Stonehouse I discovered a Cotswold escarpment on Haresfield Beacon and during several afternoons made up a guidebook (unfortunately lost) to various little routes on it, the most difficult, after several attempts, being an overhanging groove, only conquered when I discovered the arts of ‘bridging’ on vertical walls. I think John Kay, who was with me that day, probably looked up with some horror! That technique proved a necessity when pioneering a new traverse of the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy in the Colombian Andes when I was on a Cambridge expedition in 1959 which also included the first ascent of a shapely little snow and ice peak called Picacho (see the photo). We mistakenly called it ‘Picasso’ to the amusement of the Colombians!

A degree of freedom allowed us to sample many ‘outside’ sports. I remember in my last year cycling to Tewkesbury with Dai John to hire a yacht on the Severn. I had no experience of sailing but Dai did and he taught me, after going with the wind, how to tack laboriously back upstream while a younger party from our House sped by laughing in a motor boat they’d also hired!

Back in my first year, at Cambray, before proceeding into Wards House, we discovered in Claud (‘Beaker’) Allen’s garden store a set of golf clubs and practised with them some evenings on the cricket ground. Then I had the idea of taking them on a free afternoon by bus to Minchinhampton to play on a real course. This I did about three times, usually starting on the 4th tee to avoid querulous eyes in the club house, joining once a party of seasoned golfers. The curious thing was that, although I played golf seriously in my 60s, I probably played better on those few occasions than I have ever played since, because although I didn’t hit the ball very far it always went straight!

Unfortunately, on returning the last time Beaker was waiting for me and I was rightly (in those days) given a severe, prolonged punishment. At the end Beaker said, ‘And how did the Grade 5 go (a piano exam I had taken that morning)? ‘Rottenly!’ I sobbed.

True. I failed it through lack of practice, but I made up for that eventually twenty years later when I managed to pass my LRAM. As my piano teacher Beaker emphasised in my first lesson the virtues of a bent finger by drumming his on my skull. As a pianist himself he was magnificently athletic and in concerts, for instance, we were bouncing in our seats to the sound of his skilful rendering of De Falla’s Ritual Fire Dance.

Beyond my childhood, when I was listening to my mother’s brilliant and soulful piano playing, I owed most of any musical ability I developed to the dedication of the Rev T.S. (‘Bag’) Dixon (how did he get that undeserved nickname?!). How many music teachers run a never ending annual round of G & S productions, school and chapel choirs, house competitions and concert after concert as well being a housemaster? I chose to be an alto when I arrived, probably the best musical decision I ever made (how important a sense of harmony is) and then bass later. In my final year I had to step in late to take the tenor part of Ralph Rackstraw in HMS Pinafore and Rev. Dixon spent half one night transposing the orchestral parts to accommodate my voice in some of the songs. I wish I had shown appreciation at the time for his care. Curiously it was some of his classroom idiosyncrasies that remain in my memory. How many of my contemporaries remember the ‘knock of fate’ inside his store cupboard for the opening of Beethoven’s 5th, or what Augustus Harris had for his tea to illustrate the subject of one of Bach’s fugues? (From the 48, Book 1, No 16 – Answer: an egg!)

My mountaineering ambitions faded somewhat in the 1960’s unlike those of John Cleare who became a dedicated Himalayan climber and photographer. Instead I became a bit of a ‘jack of all trades’ as I turned to drama, English teaching, and then music. After studying Geography but failing to get a degree at Cambridge, due partly at least to my inability under exam conditions to create essay type answers to questions (a topic I fiercely debated later), I jumped through various employments: insurance clerk, mountaineering instructor, office work in Bostik Ltd, becoming ‘unstuck’ from this last post to enter Matlock College of Education to gain a teaching diploma. Whilst studying again I became immensely keen on English and Drama, President of the College Dramatic Society, concluding my two years arranging a production at the Edinburgh Festival.

My immersion in theatre should have finished when I began teaching, but in my first year in schools there were dramatic upheavals. The Nottingham authority, contrary to acceptable practice, I am sure, switched me from the school I had chosen to one that was understaffed. There I found a ferocious headmistress who required me to submit every day a programme of lesson notes, frequently entering the classroom herself, and requiring a report later every day after lessons finished. One previous probationary male teacher, I learned, a PE specialist, subjected to the same treatment, told her to put her shorts on, take over, and then walked out!

And so did I, not quite as outspokenly. Instead I simply went to the recently opened new Nottingham Playhouse, where as it happened I had been acting as an extra in a production of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, and they offered me straight away the job of stage hand and more little parts. It was a memorable two months as I was working alongside some of the best known actors of today: Ian McKellen, Judi Dench, Michael Crawford and others. John Neville, in particular, was a superb player and director and was very encouraging concerning my efforts.

I might have stayed there, but something inside me told me not spend my life acting the parts of other people but to return to teaching which I managed to do, in Derbyshire, thanks to an Everest mountaineering old friend of my father’s, Sir Jack Longland, chief education officer in that county. But my problems didn’t end there.

I was passionate about creative English teaching (still am) knowing that fluidity is the very essence in the development of one’s language and comes from reading, listening and self expression. All else follows. My new headmaster unfortunately didn’t agree with subordinating spelling, punctuation and grammar and told me that with my methods I would not find a school anywhere, so I advertised in The Times and after receiving six positive replies moved to Surrey.

During these turbulent years after leaving Wycliffe there was one person with whom I corresponded who kept a fatherly eye on me, none other than the headmaster himself, George Loosley. Three times I was invited to visit him, first during my National Service to his new house in Wycliffe grounds, and later with my mother and uncle to his retirement home above Stroud. Doubtless he felt for me the early loss of my parent, the Everest mountaineer and author Frank Smythe, and I felt very sad when he himself and his dear wife passed away, too soon after retirement.

One of the questions George (‘Stan’ to us boys) put to me was what did I regret about missing at school. ‘Not doing enough reading,’ I said. But this was because it was sport that enthralled me at Wycliffe, even though I was not in the top flight of teams. It certainly was not the fault of our English teacher, Mr Despres, who, like Stan, took great, kindly interest in us boys. ‘Not bad for an uncle,’ he once said as I sped past the opposition in a practice rugby match to score a try.

That occasion brings to mind the eventful early career of my elder brother John who, within three years, was Head Boy at Wycliffe, left early to start his National Service, to be commissioned and posted to Austria in the Royal Signals, then married after a year. On completion of the service he worked as a farm hand while he took his ‘A’ levels and then started a law degree, and a family. My other brother, incidentally, also left Wycliffe early and after being a local press photographer entered the RAF and became a pilot. I remember watching and admiring from our home in Northampton his manoeuvres for which he received an award.

One year in Surrey, 1967, 12 years after leaving school, put my life on a straighter path. I got married and our family was on its way. A rather more curious incident helped to determine my career as a music teacher. I had been reading books by David Holbrook on the subject of creative English teaching. I even corresponded with him about my problems and received much encouragement. But it so happened that his writing in some measure pointed me towards musical expression, for in his book, The Secret Places, he quoted extensively extracts from Aaron Copland’s Piano Sonata, with its striding, harsh chords, as inspiration for young listeners to understand some of the turmoils of modern life in a metropolis

This caused me to practice the demanding first movement of this work and, for good measure, play it at the Brighton music festival where I won the recital cup, which led to a series of other entries where I sometimes succeeded also. ‘Oiseaux Tristes’, a beautifully evocative work, from Ravel’s Miroirs Suite was a particular success at the Hounslow festival and the adjudicator there, Guy Jonson FRAM, subsequently gave me lessons which resulted in my LRAM later.

Meanwhile we had moved closer to my former homeland in Northamptonshire where I changed to teaching in primary schools, developing and creating music with these younger children. How much more one was appreciated for this kind of work! I wrote music for their festivals with neighbouring schools which eventually led to my final class teaching post, head of music in a Telford secondary school.

This is not say it was now an easy, natural ride for me. Quite the opposite. It was a colossal struggle establishing music in this particular school where I spent 13 years. To start with there were weekly lessons in an ordinary, small classroom with a total of 600 pupils spread over 20 classes and no practice area save a small room next door used for medical inspections and the occasional visit of a brass or woodwind peripatetic teacher. In addition to this, of course, I was expected to produce the perfect carol concert and accompaniment on any special occasion. Fortunately a new department was built after my first two years and eventually a change of administration allowed less anguish in the classroom and more development of choral and instrumental music. Even so it was the most testing time of my life but also the most precious moment of my career. Pure, natural voices in my choirs (see the Shropshire Star photo of 1981) and the dedication of some of my brass and wind players live in my memory like jewels in what was initially a hostile, barren land.

I used to squeeze my small two-part choir into the school minibus to travel to festivals and on one occasion after arriving one of my singers said to me tearfully, ‘Sir, they’re laughing at us because there’s so few of us.’ ‘It’s not the quantity I replied, but the quality….’, which brings to mind the adage oft repeated at Wycliffe, ‘If it’s worth doing it’s worth doing well.’ We won the cup incidentally.

Success came also in festivals that I organised myself with local schools in Telford and Newport, Shropshire, where we lived. Much of the music played and sung I arranged or composed myself.

After retiring from class teaching I taught for another 20 years privately and as a peripatetic at schools like Adams Grammar School in Newport, Wrekin College and St. Dominic’s, Brewood. I published articles in Music Teacher, concert reviews and a book of poems, and wrote other books (unpublished!). Perhaps the most unusual assignment came at Christmas, 2008, on the retirement of our local primary school head teacher. To celebrate the occasion he asked me to produce a nativity play involving every child in the school, over 200 of them. I hesitated slightly, but needn’t have done, for after I had written a script he helped rehearse the different classes with the unusual carols, songs and scenes I had devised and set up staging, lighting and so on. He was a ‘hands on’ head teacher who led from the front, which reminded me of the best heads I have experienced, including, of course, George Loosley.

After retiring from teaching altogether and moving to West Sussex I began playing the piano and the flute, my second instrument, at our local church, including improvised flute descants. Round the corner from our house I became involved in dramatisations of bible stories at the village primary school. With incidental music as well for Age UK meetings (my wife, Kathy, made cakes) we became quite busy again. All this, of course, came to a sudden halt as Covid-19 struck. What next? Like nearly everybody we hope for active, social times still.

Looking back, Kathy was a young, hospital nursing sister when I met her. We rapidly had three children, two of whom became teachers like me. Andrew, our eldest is now a head of science in a very large London school (a department of twenty five, not one like mine!), Sarah, a violinist in various baroque orchestras, now helps to run the Lewisham Music Service. Zoe, the youngest, assisted us in venturing to some remote places in our ageing years including South West China and the Kimberley outback in Western Australia, as these were some of the places she worked as a GP.

I like to think that our children and the seven grandchildren that followed have inherited the spirit that my brothers and I developed, thanks, in no small measure, to a school like Wycliffe College. Most of the staff, in addition to those already mentioned, showed kindly, personal interest in us boys and our background. I think of my Wards housemaster, Mr Wilden Hart, in particular because, too late now, I owe him an apology for an entry in the Wycliffe Star shortly after I left, which asked him to let me know when he next organised an outing to the Brecon Beacons so that the RAF Mountain Rescue to which I then belonged might be on stand by (remembering his previous trip when the party got slightly separated in misty conditions near the top!) He must have been more than a trifle embarrassed which was unjust, considering what an excellent and kind teacher he had been.

Another most memorable and committed housemaster was the geography teacher, Mr. R.B. Evans of Haywardsfield. His lessons had a vibrancy as he breathlessly described the regions of our planet. After seventy years I believe I recall, more or less correctly, his crescendo description of our East Anglian Fenlands as possessing a ‘rich, black, sticky, loamy soil’. But his responsibilities went much further than those within the school for, as the officer in charge of our ATC, he spent enormous time driving parties of us in his vintage car (was it an Austin 7?) to an RAF station to enjoy the unique experience of being flown in light aircraft such as the Harvard, sometimes being taught to control them. I remember that as we approached the airfield we invariably heard his command, ‘Hats on, chaps!’

Hats off, I say, to all those staff at Wycliffe who gave us so much care and experience.