P J W 1951 - 1958

It is always interesting to receive an email from an OW who wants to share a little of their life story with us, particularly when it turns out to be something quite pioneering that they have gone on to do. An email from V Graham Roberts was just that.

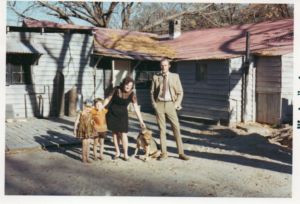

Graham had recently written an article for a local magazine and was moved to send it to us. He was at Wycliffe from 1951 to 1958, and he says “My inspiration to travel came from talks given by the Siblys, and from visitors like Peter Scott. The period spent in Crewe Locomotive Works was between my years at Wycliffe and going to Manchester University. The period spent working for Zambesi Saw Mills was from 1970 to 1976. I later went on to work in Venezuela, Nigeria, Colombia and India.” Both Graham’s children, featured in the photograph outside their house in Mulobezi, Roland (J W 1976 – 1982) and Elvire (HE 1982 – 1984), attended Wycliffe too.

Crewe Works Stripping Pit to the African Bush – memoir of a railway worker.

The previous four generations of my family worked for the London and North Western Railway at Crewe, so the L&NWR runs in my genes. My Great-great Grandfather was an engine driver at Crewe in the 1840s; his son, my Great Grandfather, was a foreman in Crewe Works; his son, my Great Uncle was a fitter in the works; and my Father was in charge of the experimental department, responsible for development and testing of steam and diesel locomotives.

I always dreamt of following in my forebears’ footsteps, so in 1960 I went on a Short Works Course in Crewe Locomotive Works, which involved working in every major department. One was the Erecting Shop, where they were still maintaining steam locomotives, although diesels were starting to take over. As was the tradition, the first job for a “green” apprentice was to put him in the Stripping Pit. On my first day, the foreman said ‘Right, Roberts, go down in the pit and remove the centre pin from the front bogie of that Class 8F’. So I clambered down into the pit, and crawled to the bogie, only to find that it was covered in dead pigeons, a dead dog and a thick layer of greasy dirt; all of which had to be removed before I could access the centre pin. My next job was to remove the coupling pin from the cast iron drag-box under the cab, which was also covered in dirt and grease.

The Short Works Course was a wonderful experience, but it brought home the fact that steam locomotives were rapidly disappearing, and diesels were taking over, which shattered my dreams. After giving the matter some thought, I decided to change direction, and trained as a Civil Engineer, working on railroad tracks, bridges, highways and power stations.

Following several years in the construction industry, I really wanted the opportunity to travel overseas. The company I was working for had a lot of projects in South America, but when I went to see the Personnel Manager I was told that I was at the bottom of the list: ‘First we send bachelors, then married couples; you are married with two children, so no chance’. Amazingly, at this point, there was an advert in the Sunday Times for a “Railway Executive Engineer – Zambesi Sawmills Railway, Zambia”, offering a very good salary. I hadn’t a clue where Zambia was, so I looked in our atlas, and found it was in the centre of Africa; I also discovered that the railway was the largest privately owned railway in the world, and the trains were hauled by elderly steam locomotives. As I’d only just turned 30, I thought my chances of getting the job were very slender, but decided to put in an application. Immediately there came an invitation to attend an interview down in London, so feeling very pensive I made my way there. What I did not know, was they’d been advertising for six months and had received no other applications. Consequently, when I sat down for the interview, the first question they asked was ‘When can you start?’ My reply: ‘4 weeks from now’. I got the job.

The headquarters of Zambesi Sawmills were at Livingstone, just by the Victoria Falls. Timber was extracted from the forests and taken by temporary railway lines to a sawmill at Mulobezi, (100 miles northwest of Livingstone), where it was processed; then the timber products were transported down a 100 mile long railway line to Livingstone, and the wagons transferred to Zambia Railways for onward journeys to the customers. Several of the temporary branch lines into the forests were over 70 miles long, bringing the total length of the railway to 300 miles. It was served by 29 steam locomotives, some being built in the 1890s.

I arrived in Livingstone at the beginning of November 1970, to a warm welcome from the staff. However, I could sense a feeling of reservation amongst the much older railwaymen, as if they were thinking ‘What does this young green-horn know about steam locos and railway track?’ The two senior foremen took me around the railway yard in Livingstone, quietly bombarding me with technical questions, which I managed to answer; finally, we approached a big lump of cast iron lying half buried in the sand; ‘Do you know what that is?’ they asked; ‘A drag-box from a Class 7’, I replied. They gave me a big smile – I’d passed the test! My time in the stripping pit at Crewe Works had not been wasted.

During the next six years, I continually drew on what I’d learnt during the Short Works Course, and the skills passed down the generations of L&NWR employees, particularly the ability to solve practical problems.

The main workshop of the Zambesi Sawmills Railway was at Mulobezi, where my family and I lived. Part of the workshop included a brass foundry (see photo below) where we made castings for various items, particularly the bearings for loco connecting rods and coupling rods, which wore out quickly due to the track being laid on Kalahari sand. The foundry foreman, Mukwe, oversaw the making of the wooden patterns, setting up the moulds and then pouring the molten metal into the moulds. Everything was working fine, until several of the brass bearings began to crack, even though they were hardly worn. Fortunately, I had a contact in Rhodesia Railways’ works at Bulawayo, so I sent him a broken sample to see if he could identify the problem. He carried out a Spectrometer test to check the chemical constituents, and found that there was a shortage of Antimony, possibly because we’d been overheating the molten metal and boiling it off. So we added some Antimony and reduced the temperature of heat to the crucible, and we had no more brittle fractures. One lives and learns!

The branch lines in to the forests were continually being lifted and relaid as extraction of the timber progressed. There were no mechanical aids; all the lifting and laying was done by hand – one man could carry two metal sleepers, and a rail needed four men. The track gang worked on a “job and finish basis”, so they often ran with their load, whilst singing and joking, until the day’s target had been achieved. One of the great things about working with Africans in the bush is their sense of humour and their way of solving tricky problems. The first forest line I worked on always brings back a happy memory. After setting out the marker posts for the new branch lines, I told the gang I would be back in a week’s time to check the layout; it was 70 miles from Mulobezi, so I asked the foreman how I would find which branch they were working on. ‘Don’t worry Bwana, you will find us; just drive towards Namazingu’, was all he said. So, a week later, I drove towards the forest wondering if I’d find the gang in the large area involved. Suddenly, in the distance, I spotted a corn dolly (see photo below) and followed the direction it was pointing; then I followed several more corn dollies, and eventually found the gang busy working. ‘Bwana, you have found us!’ the men shouted, falling about with laughter. I’d passed Test No.2.

Very few of the men could read or write; so when it came to a specific project, such as building a new bridge, there was no point in producing any documents. We just sat in a circle on the ground, every morning, and drew in the sand what was to be done that day. The job was always built on time, and to budget. Life was nice and simple in the African bush.

My railway ancestors must have dealt with similar circumstances over the years since 1840; not only those who spent their time in Crewe loco works, but also another Great-great Grandfather who was a railway labourer in Market Drayton.

Once railways are in your genes, you can’t get rid of them!

[Notes: 1) L&NWR Society Journals for June and September 2007 contain an article “Five Generations of Railway Workers” about the writer’s forebearers. 2) A book entitled “Sitimela” by Geof M. Calvert gives an excellent history of the Zambesi Saw Mills Logging Railway. 3) On the web, by googling “The Man Who Loves Giants – David Shepherd – YouTube”: the first half hour is a BBC film of the wild-life artist David Shepherd on the Zambesi Saw Mills Railway; (original title “Last Train to Mulobezi”). 4) The timber harvested was Zambesi Teak (Baikiaea plurijuga), very dense, hard, strong and durable. 5) One of ZSR’s locos, ex – Cape Government Railway No 390 (South Africa Railway No 993), was given to David Shepherd by President Kaunda of Zambia; the loco is now on display at the National Railway Museum, Shildon; by coincidence, it rests alongside LNWR locos Hardwick and Cornwall. (Also ZSR coach, ex – Rhodesia Railways No 1808, is in storage at Wroughton, waiting to join the locomotive.)]

This photo shows the family smartly dressed – a very rare occasion! Left to right is Elvire Roberts (OW), Roland Roberts (OW), my long suffering wife Maureen (Crewe Grammar School), our Rhodesian ridgeback dog Sarie and myself (OW). The photo was taken outside our “lil’ ole shack by the railway track” in Mulobezi.

Zambesi Saw Mills staff – Just a few of the staff at Mulobezi (we employed over 1000 people). I’m the one in the middle, wearing spectacles.

The brass foundry

A corn dolly